A Note on the Berkeley School of Criminology

The Berkeley School of Criminology was founded in 1950, largely due to the work of August Vollmer, who had been Berkeley’s Chief of Police, as a professional training school for police officers and penal administrators (Dombro, 2022). Austin Harbutt MacCormick, a career prison reformer, who had previously been head of corrections in NYC in the 1930s and was responsible for overseeing the first years of the newly constructed Rikers Island penitentiary until it began to experience the usual challenges of poor conditions, brutality, and despair, was appointed Professor of Criminology at Berkeley in 1951, becoming Acting Dean of the School of Criminology before he retired in 1960.

August Vollmer in 1936, with the president of Berkeley, Robert Sproul Source: San Francisco Digital Archive, Dombro, 2022

It was in the late 1960s that Berkeley became caught up in “the spirit of the times” with the explosion of civil rights, anti- Vietnam War, Black Power, and Women’s Liberation protests politicizing and encouraging activism among students and faculty at university and college campuses both nationally and internationally (Mooney, 2019). In such a climate it was not surprising that the Berkeley School of Criminology abandoned its administrative focus and became by the early 1970s, as Barak and Pagni write, “with Herman Schwendinger, Paul Takagi and Anthony Platt in residence…home to the west coast enclave of radical criminology” (2010, p.162). Others associated with the School included Richard Korn, Elliott Currie, Gregg Barak, Krisberg, and the radical social psychologist, Aviva Menkes (Barak, 2020).

The School attracted an eclectic group of Marxists, Maoists, left-liberals, moderate liberals, social democrats, and anarchists (Schwendinger et al, 2002, p. 42). Julia and Herman Schwendinger recalled this resulted in, a vibrant intellectual climate. Fundamental political and economic questions were raised about America’s class, gender and racial inequality. And interaction between radical students and staff brought about the critical mass that produced an Enlightenment- like explosion of rich theoretical ideas about the nature of crime and criminal justice (ibid, p. 43).

The Berkeley criminologists questioned the presumptions and parameters of mainstream criminology: state definitions of crime were contested and a Marxist tradition, that especially built on the work of Rusche and Kirchheimer (1939), was, as Myers and Goddard write, led to a, “a powerful tool for understanding why the crimes of the disempowered are disproportionality defined as crimes and why the ‘crimes of the suites’ go largely ignored by the US criminal justice system” (2018, p.14). For the Berkeley criminologists, understanding how the mechanisms of social control operated was of utmost importance, for, “punishment, criminal law, and the institutions of the justice system are better understood as a mechanism to manage labor and facilitate social control processes” and “social control creates deviance, not the other way round” (ibid).

The School attracted a number of visiting scholars and fellow travelers, including Marie Bertrand, from the University of Montreal, John Irwin, the formerly incarcerated penal reformer who was to have a profound influence on the development of convict criminology, David Du Bois, editor of the Black Panther newspaper and the son of WEB Du Bois, Richard Quinney (see Barak, 2020), Stan Cohen, Mario Simondi from Italy, and Karl Schumann from Germany. Cohen, Simondi and Schumann arrived in 1970, sharing an office. Thus, at Berkeley there was a coming together of key people involved in the emergence of North American and European critical criminology and, as van Swaaningen notes of Cohen, Simondi and Schumann, even though they did not know each other previously, they shared “a dissatisfaction with the dominant law-and-order interests” which determined the criminological agenda and “a positive commitment to social justice” (1997,p. 82). Mario Simondi, Stan Cohen and Karl Schumann, with Ian Taylor, were instrumental in creating a European version of the UK’s National Deviancy Conferences – the European Group for the Study of Deviance and Social Control – that was described by Stan Cohen as “as an instrumental force in bringing together like minded scholars”[1], similar to the Berkeley School of Criminology project.

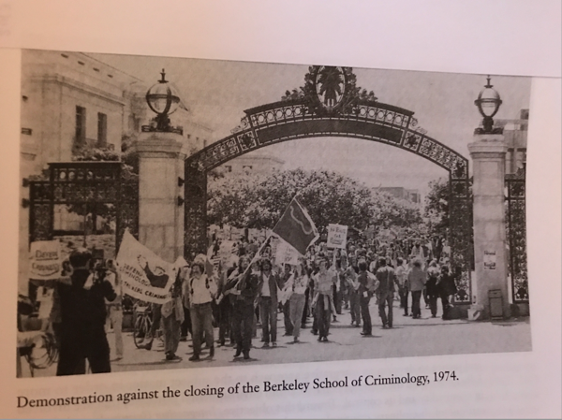

The radicalism of the Berkeley School, its association with the Black Panthers, active opposition to the Vietnam War, support for prisoners’ rights and abolitionism, and the formation of the Union of Radical Criminologists, a faculty-student organization (Barak and Pagni, 2010), was met with opposition from conservative forces both within and outside of the university – as high up as the then- governor of California, Ronald Reagan, and President Richard Nixon – who were committed to a law and order political agenda and a “friendly fascism.. bred by decades of McCarthyism and the Cold War” (Schwendinger et al, 2002, p. 48). Herman Schwendinger and others were denied tenure as a direct result of their political views (Schwendinger’s having been expressed in Sociologists of the Chair: A Radical Analysis of the Formative Years of North American Sociology [1974, with Julia Schwendinger]), the budget was cut and the school eventually disbanded. [1] the European Group held its first meeting in Florence in 1972 and still holds annual conferences today (see europeangroup.org).

Yet the legacy of the Berkeley School of Criminology lives on: as Myers and Goddard point out, many of the radical Berkeley faculty and doctoral students have continued to influence and inspire those seeking a critical perspective, and to modify, broaden and challenge the “core ideas” of mainstream criminology and criminal justice (2018, p. 218; see also Barak, 2020). Moreover, the Berkeley School’s journal Social Justice, founded in 1974, remains well-known for publishing works that expand the “horizons of criminology” (ibid) – at the time of writing the last issue included Anthony Knowles on “Universal Basic Income, Social Justice, and Marginality: A Critical Evaluation”, Brittany Arsiniega & Matthew Guariglia on “Police as Supercitizens” and Ralph Armbruster Sandoval on “Crossing the Line(s): The School of the Americas, Radical Pedagogy, and Sacrificial Activism’ (2022, Vol. 48-4 http://www.socialjusticejournal.org). “The scholarship produced at the Berkeley School of Criminology not only predicted mass incarceration and the expansion of crime control into all corners of daily American life (and the racialized and classed nature of that expansion), but they predicted what appears to be the only way to combat it: a social and political movement” (Myers and Goddard, 2018, 219).

The Berkeley School: a critical teaching agenda 1972–1973

(excerpt from Jayne Mooney’s “The Theoretical Foundations of Criminology: Place, Time and Context”)

In the fall–winter quarters of 1972–1973, Tony Platt, Barry Krisberg and Paul Takagi revamped Berkeley’s Introduction to Criminology course. The syllabus was published in the Newsletter of the Union of Radical Criminologists under the heading “The New Criminology: A Course Outline”. The introductory course had previously been taught as a public relations course for non-majors, featuring a conventional survey of the field (Platt et al, 1973).

As the authors of the new course wrote, it was to cover the following in the first quarter: “The Definition of Crime (Who Are the Real Criminals?); Ideology and Scholarship; Theory and Practice; The Crimes of Imperialism; The Crimes of Capitalism; The Crimes of Racism; The Crimes of Sexism; and Crimes by the State . . . we argued that the traditional (legal) definition of crime and criminology was grounded in liberal conceptions of society, served to legitimize inequality and exploitation, and restricted the field of criminology to narrow and technocratic social engineering. We argued instead for a human rights definition of crime which expanded the legal definition to include system crimes (the political economy) and state crimes. We proposed that legally defined ‘criminals’ were the victims of larger crimes such as imperialism and racism which denied whole classes of people (even countries) their full human potentiality and right to survival, self-determination and dignity”. (ibid, p. 11).

In the second quarter they “examined social control and the criminal justice system, emphasizing a class analysis, historical perspective and political economic framework” and included topics such as ‘Marxist Perspectives on Social Control’, ‘The Political Economy and the Rise of Modern Social Control Agencies’ and ‘The Rise of the Modern Criminal Justice System’. As Platt et al note, “liberal theories of control were presented and critically rejected” (ibid, pp. 11–12). They assembled their own reader, which included a core of radical texts, for example, George Jackson’s Soledad Brother; Mao Tse-Tung, On Practice; Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Colonial Wars and Mental Disorders; Harry Magdoff, Imperialism: A Historical Survey; Ralph Miliband The State in Capitalist Society; and Juilet Mitchell’s Women: The Longest Revolutionand showed movies such as the Battle of Algiers and The Murder of Fred Hampton. Nearly 600 students took the first part of the course, over 300 the second, making it “the largest number ever to take a criminology course at Berkeley” (ibid, p. 11).